Les mistons

Francois Truffaut’s second film Les Mistons (France / 1957) - after his silent debut Une Visite three years earlier – had initially been planned as a feature-length project that should have featured several episodes concerning themselves with the way how children view the world. As Truffaut stated on numerous occasions, at the time he was filming Les Mistons, he saw the role of children presented in contemporary french films as clichéd and marginal. Because of his own difficult childhood, it is understandable that such a topic lay close to Truffaut’s heart. What he wanted to achieve through his depiction, was an uncensored and raw feel of childhood, an observational distance that wasn’t judgmental per se, but which instead would be able to give the viewer an authentic portrayal that could lead him to draw his own conclusions.

Luckily, if I might say so, the whole project didn’t evolve as imagined, with only one episode remaining, which now comprises the seventeen minutes long short-film Les Mistons ultimately became. I say luckily, because otherwise we probably wouldn’t have his subsequent film Les Quatre Cents Coupes (1959), as its storyline should have been included as one episode of the compilation, and who knows how film history and The Nouvelle Vague would have developed without it.

Les Mistons was made on a shoestring budget and is overall an uneven film of a young director who is still searching for his own voice. The film is jam-packed with cross-references and a specific agenda Truffaut developed earlier in his critical writings for “Les Cahiers du Cinéma”, but while similar films could seem overburdened, the fragmented approach doesn’t hide the films deficits, but points to a richness which one would wish to have been further explored. So the opposite of most student-films is happening here, with the film not being too long, but instead far too short. Though it still works as a coherent whole, to me it seemed more of an appetizer for bigger things to come.

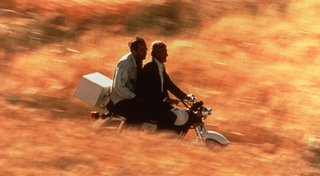

The plot is a deceptively simple one, concerning itself with the pursuit of a beautiful woman by a group of five kids, who try to play tricks on her and her lover because of their inability to approach her on a personal level. Curiously it is an adaptation of a short story by Maurice Pons, with the literal text being used as a voice-over throughout most of the film.

What makes Les Mistons a rewarding experience is the enthusiasm that can be felt from all people involved. Truffaut’s love of cinema and its possibilities is evident in every frame, with his references to film-history and the filmmakers he was previously championing in his writings all over the place. The poetics of people moving through nature obviously from Renoir while Cocteau is honored through various slow motion shots and a resurrection scene that could have come straight from Orphée (1949).

My favorite moment of the film appeared when Truffaut was paying hommage to the Lumiere brothers with almost a film within the film. Complete with a “silent” piano score and the accelaretad movements of people on-screen (wich were common when silent films were screened throughout most of the sound-era, because of a wrong projection speed) the famous L’arroseur arrosé (1895) is recreated, with a slight but important difference. While the camera in the earliest films remained static, hindering the comic impact of some films, through the insertion of a singular close-up, Truffaut shows how the lessons on suspense taught by Hitchcock can be successfully applied to achieve a comical impact. In the end, thriller and comedy are the two genres which are most dependent on timing.

The exit from this unrelated scene to the main narrative is also remarkable, in that it doesn’t happen through a mere cut-away to the storyline, which would have - with someone less experienced in film history - merely resulted in a perplexed viewer. Instead Truffaut chooses to connect this small event with the rest of the film through a zoom-out and the entrance of Bernadette Lafont into the frame. But this is not only one more example of his concern and respect for the audience, which would in his later career lead to accusations of pondering to the masses, but much more importantly the one essential gesture which links Les Mistons symbolically with the whole past of cinematic history. In this moment the present and the past lose their preliminary importance. The same goes for the films voice-over which tells of the past when the film is rooted in the present of France in the 50s, while the stylistics and ideology of the filmmaker are pointing to the new Wave of the 60s. Time becomes meaningless, interchangable as can be also witnessed in the films fragmented approach towards the narrative.

The storyline is itself told in a casual, seemingly unrelated manner, when events are merely lined-up like pearls on a string and causality loses its importance. If one counts the times in which Bernadette Lafont is shown riding on a bicycle even the argument of this scenes importance as Leitmotif can’t help to illuminate why it is featured in this large extent. Maybe Truffaut was as fascinated as the “mistons” with Lafont in her first acting role. Though she is the main focus of attention, her character is the least developed one and one could complain about her being used merely as a projection screen for the male fantasies if that wasn’t exactly what the film is about.

Nevertheless the film shows one weakness of Truffaut as a filmmaker which would become exemplary in his later work. He seems somehow to mistrust the image, shortening its impact through the voice-over. While in some scenes a welcome edition, as the film unfolds the unnecessary nature of the narrator becomes more and more obvious. At times the text feels almost forced on the images, having nothing to do with it, when the disharmony between the precise language and the liberated images doesn’t enrich the two but brings the whole film down to a level where accident and the viewers taste overshadow the films intentions. Though the structure was clearly an inspiration for later filmmakers like Jean Eustache - Les mauvaises fréquentations (1963) and Le père Noël a les yeux bleus (1966) - I feel that the voice-over wasn’t used in favor of the film. Some of this uncertainty and mistrust can also be felt in the humorous dialogue which sometimes feels forced and arbitrary. Truffaut is clearly more at home with the control a narrator can offer. The more satisfying associative part the viewer has to handle, finds its most successful outlet at the end of the film. When the death of Bernadette’s lover during a climbing session is revealed through various newspaper articles, it is clearly the effects of the Algerian war we are witnessing.

But the main attraction was for me the camera. Its freewheeling movements, twisting and turning in every direction, static shots contrasted with fast pans, sometimes filming from a great distance and sometimes remaining close to the characters – it is always interesting and surprising, with an eye for compositional detail. The viewpoint is never merely the children’s, the narrator’s, or that of the lovers, but keeps alternating between the three and an added third of an omnipresent observer/manipulator.

The cinematography by Jean Malige is vibrant and colorful, piercing the b&w material in away that it comes to life through the interplay of shadows in light, much in the fashion of Jean Vigo’s films. He would later also add his mastery with images to Paula Delsol’s La dérive (1964), one of the best and most neglected films of the Nouvelle Vague period. Vigo is also omnipresent in a scene which shows the kids sharing a cigarette, as well as some of the scenes between the two lovers, while his usage of silence and sound must have been a clear blueprint for Les Mistons. Ironically the fragmented approach to sound and image with its rapid-fire editing techniques and the shifting rhythm made me recall early soviet sound films and especially Dziga Vertov and his experimentations on this field in Entuziazm: Simfoniya Donbassa from 1930. As I don’t suppose Truffaut at this time was overtly familiar with Vertov, given the dislike of André Bazin towards this kind of formalism, the soviet filmmakers nevertheless had a huge impact on the construction of Jean Vigo’s own films. On a sidenote this would make an interesting discussion on the different appreciation of formal techniques regarding their deployment in avant-garde films as opposed to a “traditional” narrative. But whatever Truffaut’s own thoughts on this matter, it is a sad fact that his more experimental nature seemed to somewhat get lost in the course of his development as a filmmaker.

If we come back to Bernadette Lafont and Jean Eustache, we will see more of her beautiful eyes in his La maman et la putain (1973), and some scenes and places as well as some arrangements from Les Mistons, will be revisited in Eustaches following masterpiece Mes petites amoureuses (1974). To this day Francois Truffaut keeps influencing other filmmakers around the globe, and although his reputation among cineastes through the years has suffered considerable damage when compared to his contemporaries, that shouldn’t stop us from seeking out his films. Maybe you will find that it’s time for a re-evaluation.