Monte Cristo

Monte Cristo

(Henri Fescourt / France / 1929 / 223 min.)

Alexandre Dumas’ tale “The Count of Monte Cristo” first appeared in France in the middle of the 19th century. Published in a newspaper (something that was common practice for many writers in the 19th century, including Dostoevski), it was instantly a huge success and hasn’t gone out of print ever since. Considered a popular novel at the time of its writing it has come to be regarded as one of the best novels of the 19th century, as well as being included in many canons of world literature.

In the 20th century there have been numerous adaptations of this novel for the cinematic medium, though none of them have received any special attention outside of the time of their making. Although I have only seen a few of the many film versions - imdb lists over 50 titles associated with the novel, the earliest from 1908 – I assume that the lack of critical interest is connected to the modest qualities of the films themselves. The (mostly commercial) decision of condensing the plot of a novel that is over 1000 pages long in its printed format into a movie with a running time of only a few hours, along with a cinematic tradition which regards film as a mere illustration of a written text, has lead to many problems in the history of adaptations of Dumas’ work for the screen. Unfortunately Henri Fescourt’s Monte Cristo (1929) is no exception.

Following mostly the adventures of Edmond Dantes, the film is split into two parts with an overall running time of approximately four hours. While it remains mostly faithful to the written text, the film often falls into the trap of following it too closely without adding much of its own, although there are some moments and tableaus which enrich the story and add a fresh perspective to it. On the other hand, the producers have decided to leave out some of the underplots of the original novel, focusing plot-wise on the “important” events, which results in a rather dull retelling of the well known story. But the shortcomings of the film can’t be found in its faithfulness to the text, or the reinvention of certain moments. As can be expected, the problem lies in the presentation of these events.

As a silent film, most of the attraction naturally lies in the visual presentation. Being one of the last European big-budget productions during the advent of sound, the film affords the luxury of employing four cameramen, one of them having already worked on a serial of the same story in the 1910s. Alongside impressive shots of nature on the island of Monte Cristo and of ships at sea, the talented crew also hasn’t any problems when it comes to the characters interactions. Large crowds of people are rendered as successfully as intimate moments between tow lovers. There is even a remarkable sequence involving a murder, clearly inspired by the expressionist film, which also displays some fine editing. But while the visual poetics of the camera are in certain moments used to a staggering effect, the direction lacks the energy and imagination needed to sustain our interest throughout the entire film. Transferring such a visually imaginative writer like Dumas to the screen is a huge task, and Fescourt’s direction is lacking the courage to be original. What we get instead is a rather lifeless distillation of the novel’s narrative chord. If I return for example to the sequence depicting the murder of a public servant, the clumsy direction doesn’t match the cinematography and the editing. The timing feels somehow wrong when Fescourt tries to achieve some suspense in it, dragging out certain moments far too long. This lack of a successful rhythmic structure for the film can be felt in many scenes. A lot of times things happen too fast, with scenes being cut short, while in other moments we are stuck on events and treated to numerous different positionings of the camera that serve no apparent purpose.

A lot of the money probably also went into the interesting set pieces, and Boris Bilinsky who can be credited as being responsible for the look of the film did a very good job. The chosen locations are presented in a way that gives the viewer an authentic feeling of seeing early 19th century France come to life, stimulating his imagination in various ways. The costumes are also remarkable and add further life to the characters - something Bilinsky also managed successfully in Alexandre Volkoff’s Casanova (1927).

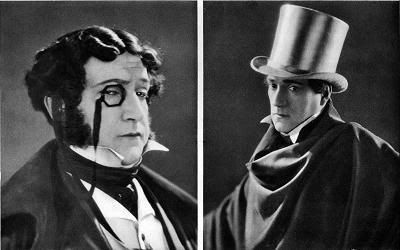

The cast assembled for this film is of varying quality. The most interesting for me was Lil Dagover who is probably familiar to most viewers because of her role in Robert Wiene’s Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari / 1920). She often plays with a restraint that wasn’t common in silent cinema and she is able to express a lot through her eyes. Some of the supporting actors are noteworthy, mainly Henri Debain in the role of Carderousse and Robert Mérin as his stepson, while others are carrying more or less the same expression on their face throughout the film (e.g. Gaston Modot who plays Fernand de Mortcerf, one of Dantes’ enemies). The bad thing is that Jean Angelo who is playing our hero Edmond Dantes and is clearly too old for the role in the first part of the film, tends to the latter. In my opinion, he has the charisma and acting abilities of a piece of wood, and the only reason I can imagine for him being chosen (besides his popularity and subsequent box-office appeal, which I will simply assume here) is the fact that he fits perfectly into the description of what we may call an honest and innocent french everyman. But while Dumas’ novel begins with this rather dull inscription, after the internment at the Chateau d’If his character goes through a transformation which will not only lead him to his outward freedom, but will turn him into a cynical and disillusioned individual after the discovery of the change in the personality of his former lover Mercedes and the life she has turned to. Jean Angelo isn’t able to display much of this on screen.

Dumas leaves the inattentive reader with an optimistic ending, in which Edmond turns his back to Marseille and its people after he has had his revenge, to travel the seas forevermore with his newly found Arabic love. But despite the skillful description of Edmond’s disentanglement from his past and the disclosure of a new perspective through his acceptance of the present - something which complements and counteracts the revenge plot - another reading of the farewell letter and the sudden departure reveals the hero’s virtual death - the noble humanistic instructions as the last words of a dying martyr. Through his death he redeems the other characters from their debt and their guilt. But isn’t this noblesse of character something which in its literally treatment verges on absurdity, and seems to mock the humanist ideals it has been promoting? Edmond Dantes, turned into some kind of Socrates after his revenge has been completed? What world is this, in which the only decent person (and the one who has gone through most of the suffering) has to sacrifice himself for the sake of others to fullfil an ideal of the enlightenment? Whatever the case might be, the novel isn’t able to resolve the inherent conflict in every human person between the forces of nature and the forces of his spirit (if I might put it this way), and it remains for the reader to decide if Dantes is all too human or the precursor of an idea which would culminate at the end of thentury in the creation of the “Ubermensch” in the writings of Nietzsche.

The complexities of these modulations can be seen only rudimentary in the film, and only in the way that they are inherent in the portrayed dynamics. This means they are present rather by accident than on purpose, and it is questionable if anybody noticed cared about it at the time of its first screening. The ending in the movie seemed to me to be a happy one, with the ambiguities from the book put aside. This isn’t a bad thing per se, but Fescourt executes it without much interest, having most of the important characters assembled in a room while Mercédès reads Dantès’ farewell letter to them. Clearly more important were the production values which can be appreciated immediately.

Although made in 1929, Monte Cristo isn’t a swan song for the silent film era. Occupying a place in the long history of adaptations of the novel, it doesn’t stand out and will probably remain only of historical interest as an example of the French film industries last silent large-scale production.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home